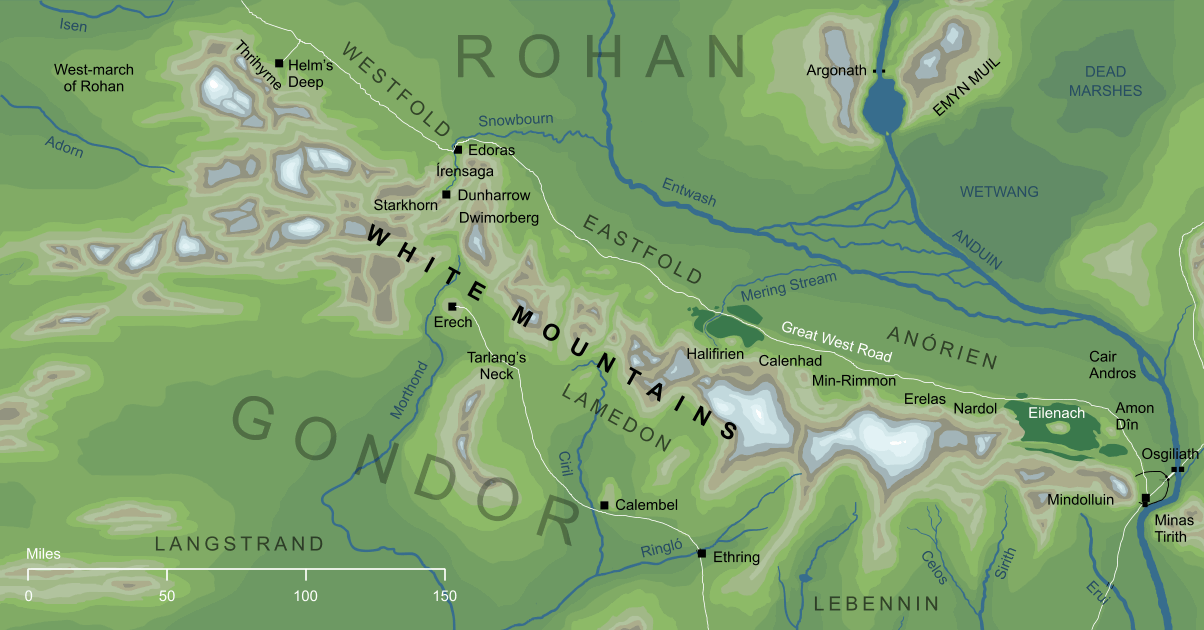

Above: The main eastern peaks of the White Mountains

1

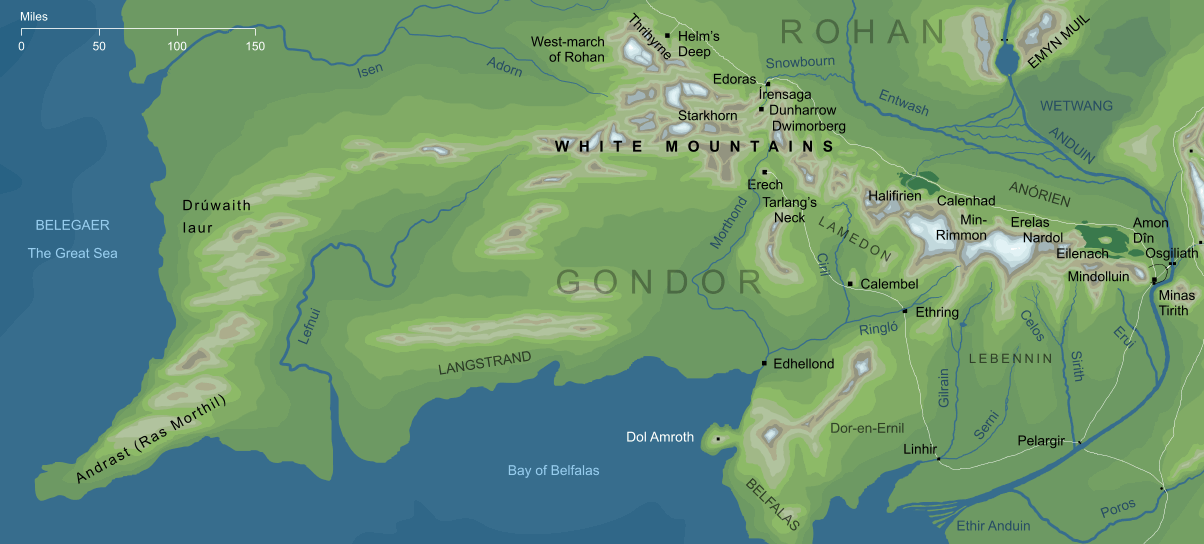

Below: A smaller-scale map showing the entire range, from the promontory of Andrast in the far west to Mindolluin in the east.

Above: The main eastern peaks of the White Mountains

1

Below: A smaller-scale map showing the entire range, from the promontory of Andrast in the far west to Mindolluin in the east.

One of the great mountain ranges of Middle-earth, running from west to east for hundreds of miles through the lands that would form Gondor and Rohan during the Third Age. The mountains are described as having blue and purple rocky walls, rising into dark peaks, and topped by endless glimmering snows that gave them their name. In Elvish they were known as Ered Nimrais, the 'mountains of the white horns', and in later times they were occasionally known as the Mountains of Gondor.

Geography

At the eastern end of the White Mountains, the peak of Mindolluin rose near the Great River. From there, the mountains ran westward and a little northward, peak after peak, until they reached the three-horned mountain Thrihyrne that marked their northern extent. The fringes and foothills of the mountains were irregular, broken by the valleys of numerous streams and rivers, especially on their southern side. Ridges and isolated peaks standing out from the main range were also common, separated from the main range by wooded valleys.

The northern spur, from which the narrow jagged peaks of Thrihyrne emerged, came close to the southern end of the Misty Mountains. At this point, the White Mountains gave way northward to a stretch of plains some fifty miles across, through which the river Isen ran, before the foothills of the Misty Mountains began to rise. This wide pass was originally known as the Gap of Calenardhon, and in later times as the Gap of Rohan.

Westward from Thrihyrne and the springs of Adorn, the great snow-capped horns of the main range gave way to less pronounced uplands. These western hills and peaks stretched on in a wide arc, ultimately reaching the shores of the Great Sea. There, they extended out into the Sea as the promontory known as Andrast, which marked the farthest western extent of the White Mountains.

In the central part of the range, two tall peaks stood close together: the Starkhorn and the Dwimorberg. From beneath the Starkhorn the river Snowbourn rose, cutting a narrow valley for itself known as Harrowdale, as it ran northward through the mountains and out onto the plains beyond. The Dwimorberg lay eastward and southward of the Starkhorn, standing above the mountains' southern foothills. In later times, a network of passageways - the Paths of the Dead - would be made beneath this Haunted Mountain, leading from the dark woods above Harrowdale through to the Morthond Vale in the White Mountains' southern slopes.

The Morthond Vale was only one of the many deep river valleys on the mountains' southern side, from which seven different river systems emerged. Between these valleys ran high ridges of rock, of which the longest ran southward for more than fifty miles, separating the vales of Morthond and Ciril. At the northern end of this long ridge, the land dipped as it approached the main range of the White Mountains, creating a shallow pass known as Tarlang's Neck.

The eastern end of the range was notable for a series of peaks and ridges that stood out from the main mass of the mountains on their northern side, where the Gondorians would build their system of Beacons. These ran from Amon Dîn near Mindolluin at the mountains' far eastern extent, westward (when the system was complete) as far as the Halifirien. This last Beacon-hill rose out of the Firien Wood, separated from the main body of the White Mountains by a gap known as the Firien-dale. Also called Amon Anwar, the Hill of Awe, on the slopes of the peak was a hidden hallow preserved by the Valar.

At the farthest eastern end of the White Mountains, as they approached the Great River Anduin, they reared into a soaring peak. This was Mindolluin, with sheer sides of dark rock and high glens of heather rising into its snow-capped heights. Beneath it to the east, a much lower hill rose, the last2 eastern height of the White Mountains. This low hill was later known as Amon Tirith, and it was the site where the Dúnedain would build the city of Minas Anor or Minas Tirith.

Ancient History

According to legend, in the earliest times of the world, the lands along the northern coast of the Bay of Belfalas were the domain of giants. Seeking to protect their realm, these giants raised a range of mountains along their northern border, a range that would become known as the White Mountains. Among these legendary giants was one named Tarlang, who was said to have fallen while building the mountains; his fellow giants continued their work around his prone body, giving rise to Tarlang's Neck and the long ridge that ran southward from that saddle in the hills.

This story of the giants is presumably apocryphal,3 and our first historical account of the White Mountains comes from the time after the Great Journey of the Eldar into the West. The main route of the journey passed far to the north of the White Mountains, but one group of Elves broke away from their fellows in the Vales of Anduin. Some of these Nandor, as they were called, travelled as far south as the White Mountains, but they did not remain. Instead they crossed through the Gap of Calenardhon and on into Eriador beyond.

The first people to actually settle in this region did not appear until thousands of years later. These were Men, of the kind known as Drúedain or Wild Men, who had been persecuted in their old homelands, and sought to escape into new lands of their own. Emerging from the mysterious regions southward of Mordor, they crossed Anduin and reached the eastern feet of the White Mountains. From there, they spread through the mountains, and eventually occupied them on both their northern and southern sides.

These Drúedain were followed by more Men travelling out of the East. After a time, at least some of these newcomers passed on northward and westward to find their way into distant Beleriand. Some of the Drúedain left their mountain homes at this time, joining themselves with the clan of Men who would later be known as the People of Haleth, and continuing with them to dwell in the faraway Forest of Brethil.

The history of Men in the White Mountains after this period is difficult to disentangle, but as the First Age ended and the Second Age began, a clan of Men occupied the White Mountains, leaving behind great works in the high valleys. These perhaps represented a branch of the Halethrim who remained when their fellows departed for Beleriand, or they may have been Men of some otherwise unknown ancestry representing a new wave of immigration from the East. Whatever their origins, these were the people who made the great stone avenues above Harrowdale in the place that was later known as Dunharrow.

This period saw an end to the peaceful existence of the Drúedain in the glens of the White Mountains. With the coming of a new people of Men out of the East, the Wild Men were driven out of the mountains and into two enclaves: the Drúadan Forest in the eastern mountains, and the lands surrounding Andrast in the far west. Elsewhere the Men of the Mountains spread and established themselves across the range.

The Men of the Mountains occupied the White Mountains into the later centuries of the Second Age, and left a legacy in the names that they used for prominent places along the range. Names like Erech, Arnach (later Lossarnach), Eilenach and Rimmon all derived from the pre-Númenórean speech of these Men. Other than these names, and earthworks such as those at Dunharrow, their history and their culture remain almost entirely mysterious. They were known to be ruled by a line of kings, though the names of those kings are not recorded. During this period, Sauron was spreading his power across Middle-earth, and the western borders of his Black Land came within a few tens of miles of the White Mountains' eastern extent. It was natural, then, that the Men of the Mountains came under the influence of the Dark Lord and began to worship and serve him.

As the Second Age drew towards its close, great events unfolded that would have dire consequences for the Men of the Mountains. In II 3261, King Ar-Pharazôn of Númenor landed in Middle-earth and marched on Mordor to challenge Sauron. The Men of the Mountains would presumably have known little of these events, but the Dark Lord they worshipped vanished from his Dark Tower when he surrendered himself to the King to be taken to Númenor. A little less than sixty years later, a great storm came out of the West, bringing the sons of Elendil to Middle-earth out of the Downfall of Númenor that Sauron had engineered.

Elendil's sons Isildur and Anárion founded a new realm in the lands that surrounded the eastern White Mountains. The lands that they claimed stretched from Mindolluin to the Gap of Calenardhon along the mountains' northern flanks, and in the south the region between the mountains and the Bay of Belfalas. In this period of history, then, the White Mountains ran through the central regions of the new land of Gondor, and for this reason they are sometimes referred to in the Third Age as the Mountains of Gondor.

The new Gondorians began to raise cities and fortresses along the White Mountains. The greatest of these was at the far eastern end of the range, on a hill4 that rose beneath Mindolluin, the last eastward peak. There Anárion built a shining city for himself on seven tiers or terraces, the city known as Minas Anor. The Gondorians built other structures farther west along the White Mountains, most notably a fortress at Aglarond to guard the Gap of Calenardhon (still standing at the end of the Third Age, this was the fortress later known as the Hornburg). On the southern side of the mountains, in a deeply shadowed valley, Isildur placed a mighty stone globe that he had brought with him from Númenor, the Stone of Erech.

The power of the Men of Gondor and their claim on the White Mountains is perhaps most forcefully demonstrated by the Stonewain Valley. Needing to carry stone to their works at the far eastern end of the range, the Dúnedain literally cut a valley through the eastern mountains. From beneath the hill of Nardol, this valley ran straight for some thirty miles, re-emerging near the Grey Wood north of Mindolluin. The route was travelled by wagons carrying stone eastward for the construction of Minas Anor, though after the tower had been built, the remarkable valley itself would eventually be forgotten.

The Men of the Mountains now found themselves surrounded by the new realm of Gondor, and their King was approached by Isildur, who ruled Gondor jointly with his brother Anárion. The King of the Mountains swore an oath to serve Isildur in the coming war against Sauron, the old master of his people, and that oath would have profound consequences. When war began, and Isildur called on the Men of the Mountains to fulfil their oath, instead they hid themselves in the depths of the White Mountains.

Isildur and his allies marched on Mordor and besieged the Dark Tower for seven years until, at last and at great cost, Sauron was defeated. Isildur did not forget the failure of the Men of the Mountains to fulfil their oath, and he laid a terrible curse on them. From that time on, their shades were doomed to haunt the mountains until they were able to fulfil the oath. The cursed people retreated to dwell in the darkness beneath a mountain that became known as the Dwimorberg, the Haunted Mountain. They lurked within the caverns and tunnels of the Paths of the Dead that ran from one side of the range to the other, from dark wood of the Dimholt on the northern side to the Morthond Vale to the south.

The Last Alliance had achieved victory in their War, but that victory came a terrible cost. Among the many slain was High King Elendil, whose remains were interred by his son Isildur in a secret Tomb. It was only long afterwards that it became commonly known that this Tomb lay in a hallow on the slopes of the Halifirien, a mountain rising out of wooded lands on the northern flanks of the White Mountains. At that time, early in Gondor's history, the mountain stood close to the central point of the realm, and Elendil's Tomb would remain there, inviolate, over the next twenty-five centuries.

The White Mountains in the Third Age

With the new land of Gondor now firmly established, the character of the lands surrounding the White Mountains changed. At the eastern end of the mountains lay the land of Anórien, the realm settled by Anárion whose chief city was Minas Anor beneath Mindolluin. From there, a road ran along the northern feet of the range, traversing nearly four hundred miles before it turned away from the White Mountains and ran towards the distant North-kingdom. Much of this land northward of the mountains belonged to a province the Gondorians called Calenardhon, whose boundary with Anórien was formed by a stream, Glanhír, that ran down out of the White Mountains near the Halifirien.

On the southern side of the White Mountains, the land of Gondor was divided into a series of fiefdoms. Easternmost of these, and closest to the more populous regions around Minas Anor and Osgiliath, was the valley of Lossarnach (whose name derived from its older, pre-Númenórean name of Arnach). Further west was a wide land known as Lebennin, the land of five streams, which took its name from the many rivers that rose in this part of the range and ran southwards towards the Bay of Belfalas. Further west still, in the angle between the rivers Ciril and Ringló, lay the region named Lamedon, and westward of Lamedon lay the Blackroot Vale, encompassing the shadowed valley of Morthond and the Stone of Erech. Beyond the Blackroot Vale was a wide, empty region, the hinterland of the Anfalas and Pinnath Gelin, continuing on westward to the springs of Lefnui. It is unclear whether this wilderness region had an independent name, but certainly none is recorded.

The Gondorians built roads on both sides of the White Mountains to connect the more distant parts of their realm to the chief cities in the east. On the southern side, the road out of the east looped far southward of the main range before crossing northward back into the foothills for the western part of its length. At its western end, it passed over the ridge of Tarlang's Neck until it reached Erech. On the northern side of the range, the road struck a much more direct path, running straight along the edge of the mountains for hundreds of miles. It was only at Aglarond, where the White Mountains came close to the Misty Mountains to form the Gap of Calenardhon, that the road left the range behind to cross Isen and lead on towards the distant North-kingdom of Arnor.

Though the Gondorians now controlled the lands around the White Mountains, barbarous peoples were said to dwell among the peaks who were unfriendly to the Dúnedain and Elves. We have one account from the period when Eärnil II reigned in Gondor (that is, some two thousand years into the Third Age) when dangerous and evil Men (and other beings more perilous) were still to be found in the heights of the mountains. Nonetheless, the lands at their feet were under the power of Gondor, and these dangers were confined to the high valleys.

Though the lands around the White Mountains were held by Gondor throughout the Third Age, across much of that Age a port of the Elves was maintained at the mouth of Ringló, one of the many rivers that flowed southwards out of the mountains. It was to this haven, named Edhellond, that the Elves of Lórien would travel if they wished to sail into the West, and the route from their northern homeland to the haven on the Bay of Belfalas led through the White Mountains.5 After the emergence of Durin's Bane, many of the Elves of Lórien made the choice to flee, and among them was the Elf-maid Nimrodel. As she crossed the White Mountains, she and her retinue became lost in the valleys on their southern side. Amroth, who was awaiting her aboard ship, became desperate not to sail without her, and threw himself into the sea as his ship departed. Thus the headland of Dol Amroth received its name. One of Nimrodel's companions, Mithrellas, was taken to wife by Imrazôr the Númenórean, and so the blood of the Elves entered the line of the Princes of Dol Amroth.

The Coming of the Rohirrim

On the northern side of the White Mountains, Gondor controlled a wide green plain that its people named Calenardhon, a land that extended westward from Anórien as far as the Gap of Calenardhon. The population of this region dwindled over the centuries, and it became difficult for Gondor to defend. This situation became critical in the year III 2510, when a raiding people known as the Balchoth launched an invasion over Anduin. The Gondorian defenders were overrun, and hordes of Orcs that had hidden in the White Mountains descended to prevent aid from coming to Calenardhon.

By this time in Gondor's history the line of Kings had come to an end, and the land was under the rule of the Stewards. Cirion was the Ruling Steward at the time the Balchoth attacked, and he found himself unable to address the threat. In desperation he sent riders to the Éothéod in the far North, whose ancestors had been allies of Gondor in the days of the Kings. Against all hope, Eorl of the Éothéod answered Cirion's call, making the long journey down the Vales of Anduin from Anduin's far northern sources to the Field of Celebrant. There he found the army of the Balchoth and defeated it, saving Gondor from the Easterling threat.

In gratitude to the Men of the Éothéod for their aid, Steward Cirion gave a great reward to Eorl and his people: the old province of Calenardhon was gifted to them as a new realm. The pact was sealed by the Oath of Cirion and Eorl, sworn beside the Tomb of Elendil on the Halifirien in the northern foothills of the White Mountains (the Halifirien now marked the border between the two kingdoms). This new realm of Eorl was known in the tongue of the Éothéod as the Riddermark, but it became more widely known as Rohan.

The people of the Éothéod became known as the Rohirrim or 'horse-lords' as they established themselves in their new land. Their many horses roamed the green plains northward of the White Mountains, while the Rohirrim established their settlements mainly along the northern fringes of the range. The central point of their realm was marked by the place where the river Snowbourn flowed out of the deep valley of Harrowdale. The mountain valleys westward of this point were known as the Westfold, and those eastward, running down to the border with Gondor, belonged to the Eastfold.

Eorl established himself on a green hill in the foothills of the White Mountains, some distance southeastwards of the point where the Snowbourn ran out of its mountain valley in a place that would be known in later years as Aldburg. His heir Brego moved the capital, establishing the royal courts at Edoras on the Snowbourn itself. There he built the famous Golden Hall of Meduseld on a hill below Irensaga, the jagged mass of mountains that rose at Harrowdale's mouth. The Rohirrim settled many other towns and villages in the valleys along the feet of the White Mountains, and garrisoned the fortress of the Súthburg (which would later be known as the Hornburg of Helm's Deep).

Brego and his son Baldor explored the White Mountains further, and as part of their explorations, they climbed up to the old earthworks of Dunharrow. There they found the way into the shadowed wood of the Dimholt, and thus to a Dark Door in the mountainside. This was the Door into the domain of the Dead, those Men of the Mountains cursed long beforehand by Isildur. After this discovery, at the feast of dedication for the newly built Golden Hall, Baldor swore to brave the darkness beyond the Door. He set off into the White Mountains to fulfil his oath, and was never seen again.

In the year III 2758, the year that the Long Winter descended on Middle-earth, Rohan was ruled by its ninth King, Helm Hammerhand. At this time the land was attacked and overrun by enemies, and the King was driven out of Edoras. King Helm retreated with his household into a valley of the White Mountains that became known as Helm's Deep. From there he raided the camps of the enemy, but at last he perished in the snows of the terrible winter. In the following spring, Helm's nephew Fréaláf was able to lead his people out of the mountains and reclaim their kingdom.

Some decades later, in the years after III 2799, hordes of Orcs appeared from the northern lands and began to make hidden Orc-holds for themselves among the White Mountains. These were the survivors of the dreadful Battle of Azanulbizar, in which the Dwarves had defeated the Orcs and brought their long War to an end. The King of Rohan at this time was Brytta son of Fréaláf, and he set about hunting down the incoming Orcs. At the time of his death in III 2842, it was thought that the Orcs had been eradicated from the mountains. In fact, some had survived in hiding, and they slew Brytta's successor, King Walda, before being slain in turn by Walda's son and heir, Folca.

Folca was a great hunter, and he swore an oath to hunt no wild beast while an Orc remained alive in his realm. He kept this oath, scouring the White Mountains and seeking out every last Orc-hold until he had rid his land of every last Orc. When he had succeeded, he returned to the hunt and rode to Everholt, a wood in the foothills of the mountains on Rohan's border with Gondor. There he met his end, gored by the great Boar of Everholt that dwelt there.

King Folca met his end in the year III 2864, and in the century and a half that followed, little of note happened among the White Mountains. Nonetheless, in the world outside events were building toward war as the power of Mordor grew. During this time, among the armies of the Steward of Gondor, the stout mountaineers raised in the White Mountains were valued as scouts, and many were posted as Rangers defending Ithilien beyond the Great River.

The White Mountains played their first, very minor, part in the War of the Ring in the days following 4 July III 3018. Over this period a figure on horseback set out from Minas Tirith and rode along the Great West Road, the road that followed the northern flanks of the mountains as far as the Gap of Rohan. This figure was Boromir, riding northward to seek out the mysterious valley of Imladris. Reaching the Gap, he followed the road away from the White Mountains and continued into the North, never to see the Mountains of Gondor again.

Some time later, on 19 September, Rohan was drawn directly into the War for the first time, when an Eagle swooped down from the north and delivered one who seemed a beggar to the gates of Edoras. This was in fact no beggar at all, but Gandalf, having escaped from the Tower of Orthanc and seeking the aid of the Rohirrim. At this time Saruman and his servant Gríma had long been working to undermine King Théoden, and so the King sent Gandalf away. It was then that Gandalf first encountered Shadowfax, and together they galloped away from the White Mountains, following the same road Boromir had taken a little over two months earlier.

On 2 March of the following year, Gandalf returned to Théoden's court with three companions: Aragorn, Legolas and Gimli. By this time Rohan had already suffered defeat in the Battles of the Fords of Isen, and a force from Isengard was making its way across the land. Gandalf cured Théoden of his malaise, and the King led his people to the fastness of Helm's Deep and its castle of the Hornburg in a valley of the northern White Mountains. There followed the only significant battle fought within the mountains themselves, the Battle of the Hornburg. Saruman sent waves of Orcs and Men against the defenders, who came close to breaking under the onslaught, but the timely arrival of reinforcements, and of the Ents of Fangorn, gave the Rohirrim a dearly-bought victory.

With victory achieved, Théoden made a brief journey to Isengard, and then returned to the White Mountains of his homeland. At Dunharrow in Harrowdale he gathered his people, and led a great force of Riders to the aid of Gondor, using the ancient road that ran along the mountains' northern flanks. As these Riders passed through Anórien, they found their course obstructed by a force of the Enemy holding the road against them. Within the Drúadan Forest, however, Théoden found a remnant of the Drúedain who had long ago lived throughout the White Mountains. These Drúedain still remembered the old Stonewain Valley made in the early times of Gondor, and the Rohirrim were able to use this to skirt their foes. Thus they came to the eastern end of the range in time to join the Battle of the Pelennor and help achieve victory against Sauron's forces.

While Théoden led his Riders eastward along the northern side of the range, Aragorn and his followers took another route. They found the Dark Door where Baldor had been lost long before, and followed the Paths of the Dead beneath the Dwimorberg. In the darkness beneath the White Mountains they recruited the King of the Dead and his Shadow Host, and emerged from the Paths on the southern side of the mountains at the head of the Morthond Vale. At Erech, the Dead agreed to finally fulfil their ancient oath to Isildur, who had been Aragorn's distant forefather. Aragorn then led the Dead on eastward, marching to the same battle as Théoden, but on the other side of the mountains. At Pelargir the Dead aided in overcoming raiders from Umbar, and Aragorn released them from their oath. He then took the invaders' ships for himself and sailed them up the Great River toward Minas Tirith. Eventually the two forces, Théoden's from the north and Aragorn's from the south, came together at the Battle of the Pelennor Fields and were able to defeat Sauron's forces there.

After the War of the Ring, Gandalf led Aragorn, the new King of Gondor, up into the snows high on Mindolluin, the easternmost of the White Mountains. There he discovered a seedling of the old White Trees of Minas Tirith, whose line had been thought extinct for nearly one hundred and fifty years. The seedling was carried back to the Citadel and planted beneath the White Tower, re-establishing a tradition dating back to the founding of Gondor at the end of the Second Age.

Throughout the Third Age, it had been thought that the Drúedain or Woses, who had once been the main occupants of the White Mountains, had become almost extinct. The only known enclave of these people was in the Drúadan Forest in Anórien. After the War of the Ring, however, many more Drúedain were discovered, in the far western mountains of the range where it ran down to the Sea. The Drúedain had long been divided into two separate branches, and the old denizens of the western White Mountains had continued to live in secret in Drúwaith Iaur through the millennia of the Third Age. So the earliest of the White Mountains' inhabitants re-emerged as the Fourth Age dawned.

Notes

1 |

The heights running from Mindolluin in the east to Thrihyrne in the west were the high snow-capped mountains that gave the range its name, but this was not formally the full extent of the range. The lower hills running westward from the springs of Adorn were also accounted part of the White Mountains. These were less high than those running through the populated parts of Gondor and Rohan, but they still formed a distinct continuation of the range. The final western extent of the White Mountains was considered to be the promontory of Andrast at the northern tip of the Bay of Belfalas.

|

2 |

Amon Tirith was formally the last eastern hill of the White Mountains before they reached the flats of Anduin. Across the river, however, another set of hills rose in a direct line from the main range. These hills, Emyn Arnen, would seem therefore to be at least geologically related to the White Mountains, though they are not directly identified as such.

|

3 |

The story of giants raising the White Mountains is apocryphal in the sense that it is doubtful whether even Tolkien himself considered it canon. Even to the people of Middle-earth, the story was presumably no more than legend (though we know that giants did exist in Middle-earth, and at least some were associated with mountains, so the tale of Tarlang and his fellows is perhaps not absolutely impossible).

|

4 |

The name of this hill is given as Amon Tirith, but this must belong to a much later period of Gondor's history, after Minas Anor had been renamed Minas Tirith. The hill's earlier name is not recorded, but by analogy with the change of the city's name, it was perhaps Amon Anor.

|

5 |

There was evidently a pass through the White Mountains that emerged on the southern side above the springs of Ringló or Gilrain. This would put the northern way into the pass somewhere in the broad 'bay' in the mountains between Min-Rimmon and Calenhad (and indeed the large-scale contoured map of this region shows a stretch of lower land running precisely where we would expect the pass to be). The details of the pass, however, must remain in the realms of speculation, as our only comment on its route (from a description of Nimrodel's journey) specifically states that the course of the pass is not recorded.

|

See also...

Aglarond, Amon Dîn, Anórien, Aragorn Elessar, Battle of the Hornburg, Beacons of Gondor, Black Master, Black Stone, Blackroot Vale, Boar of Everholt, Bree-men, Brytta Léofa, Calenhad, Caverns of Helm’s Deep, City of Gondor, [See the full list...]Dark Door, Dead Men, Deeping-coomb, Deeping-road, Deeping-stream, Derufin, Door of the Dead, Drúath, Drúedain, Drúedain of Anórien, Drúedain of Beleriand, Drûg-folk, Duinhir, Dúnedain of Gondor, Dunharrow, Dúnhere, Dwimorberg, East Anórien, East Dales, Edoras, Entwash Vale, Erech, Ered Nimrais, Erelas, Fire-hilltop, Firien-dale, Firienfeld, Firienholt, Fréa, Full Muster, Gap of Calenardhon, Gap of Rohan, Gate of Gondor, Gate of the Dead Men, Ghân, Ghosts, Gilmith, Glǣmscrafu, Glittering Caves, Gondorians, Great Road, Great West Road, Green Hills, Grey Wood, Grimslade, Halifirien Wood, Hallas, Harrowdale, Haunted Mountain, Helm’s Deep, Helm’s Gate, High Nazgûl, Hill of Anwar, Hill of Awe, Hill of Erech, Hill of Guard, Hill-men, Holy Mount, Horse-lords, Horsemen of Rohan, Írensaga, Isildur, King of Rohan, King of the Dead, King of the Mountains, Kingdom of the Rohirrim, King’s Lands, Lamedon, Legolas Greenleaf, Lord of Deeping-coomb, Lord of Harrowdale, Lord of Lamedon, Lord of Lossarnach, Lord of the Fields of Rohan, Lord of the Glittering Caves, Lossarnach, Meduseld, Men of Bree, Men of Darkness, Men of Dunland, Men of the Mountains, Mering Stream, Min-Rimmon, Mindolluin, Misty Mountains, Mornan, Morthond Vale, Mountains of Gondor, Mouths of Onodló, Muster of Edoras, Muster of Westfold, Nardol, Nimrodel, Old Púkel-land, Outlands, Paths of the Dead, Púkel-men, Riders of West-mark, Rimmon, Ringló Vale, River Adorn, River Anduin, River Blackroot, River Celos, River Ciril, River Erui, River Gilrain, River Lefnui, River Morthond, River Onodló, River Ringló, River Serni, River Sirith, River Snowbourn, Robbers of the North, Rochann, Rohan, Royal Road, Shadow-men, Silent Hill, Sleepless Dead, South-realm, Stair of the Hold, Steelsheen, Stonehouse-folk, Stonewain Valley, Stybba, Sunlending, Súthburg, Tarlang’s Neck, Tawar-in-Drúedain, The Burg, The Courts, The Dead, The Deeping, The Rock, The Starkhorn, Thrihyrne, Tower of Orthanc, Tower of the Sun, Tumladen, Underharrow, Upbourn, Walda, Water, West Marches, West-march of Rohan, Westemnet, Western Gondor, Westfold, Westfold Vale, Westfold-men, Whispering Wood, Wild Men of the Woods, Wood of Anwar, Wulf

Indexes:

About this entry:

- Updated 10 March 2022

- This entry is complete

For acknowledgements and references, see the Disclaimer & Bibliography page.

Original content © copyright Mark Fisher 1998, 2001, 2006, 2014, 2022. All rights reserved. For conditions of reuse, see the Site FAQ.